Reshaping Futures

A train rumbles through the heart of downtown Tennille, Georgia, its southbound cars loaded with kaolin, the white clay that serves as the city’s main export.

Avery Franklin sets his leaf blower on the ground, takes a seat on a park bench under a pecan tree and begins telling his story.

He was 19 years old the first time he went to jail. He’s 63 now, released four months ago after a lifetime of petty crime.

“I’ve been in and out of jail, in and out of prison,” he said. “I’ve been messing with dope since I was 18, 19.”

He’s sitting 3 miles from the Washington County, Georgia, jail cell where he spent most of the last three years of his life. Franklin now works for the city of Tennille, doing things like keeping the parks clean and fixing water leaks.

Sitting on this bench under the sun, talking over the whistle of a train bound for somewhere far away, Franklin is reflective.

“I’ve always been one who wouldn’t accept responsibilities,” he said, shaking his head. “If it was something serious I had to think about, I’d go get high.”

Something changed a few years ago as his release date drew near.

“I just got to the point where I was sick and tired of going to jail,” he said. “I’ve done that so many times. I don’t want to do that no more.”

For the first time in his life, Franklin asked for help.

Building a team

Patrick Wilson, a man better known as “Pastor P,” is in the narrow dormitory behind a maze of hallways deep inside the Washington County jail, leading nine inmates through calisthenics and stretches.

A local pastor, Wilson also is the coordinator of the Washington County Sheriff’s Office Residential Substance Abuse Treatment (RSAT) program, an intensive, six-month program for incarcerated people nearing their release dates to prepare them for re-entry into society.

Launched in August 2021 by Sheriff Joel Cochran, the federally funded RSAT program has three main components: recovery, rehabilitation and re-education of incarcerated individuals who have a substance abuse problem and a desire to change.

“We’re trying to break the cycle of recidivism,” said Maj. Corey King with the Washington County Sheriff’s Office. “We were seeing a lot of the same people come in with issues that were drug related. They’d get locked up, get released and then fall back into the same habits.”

Since its inception, 43 participants have graduated from the program and 77% are now employed. Seven have received either a GED certificate or high school diploma through a partnership with Oconee Fall Line Technical College, and nine more will graduate this summer.

University of Georgia Cooperative Extension is a major driver of the RSAT program’s success.

Georgeanne Cook, who served as UGA Extension’s Family and Consumer Sciences agent in Washington County, helped build a coalition of community partners to support the program after some initial conversations with King.

“You could say she is ever-present in the community,” King said. “Because of her, I learned that Extension does a lot more than I realized.”

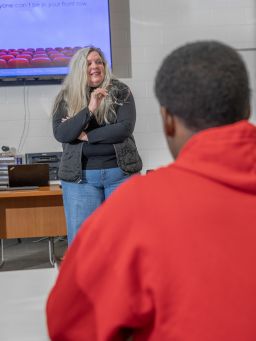

Cook taught the “Mind Matters” self-care curriculum to the first cohort at King’s invitation and recruited Conni Fennell-Burley from the Archway Partnership to lead a personality assessment program. She also identified a volunteer to lead sewing classes.

Leveraging both the UGA Extension and Archway Partnership networks as well as the Family Connection of Washington County (FCWC) program, law enforcement officials built a powerful team of community stakeholders to address generational issues tied to poverty, illiteracy and substance abuse.

Programming focuses on topics such as decision-making, character development and anger management. Graduates also receive career counseling and other aftercare services.

Many of them are employed by local businesses, and FCWC works to reconnect graduates with their families.

“The first thing that comes to mind is a oneness,” King said of the community collaboration that also includes local churches. “The people who are for bettering the community are in 100%, and they’re going to come to the table every time.”

After some nudging from Cook, UGA Extension Agriculture and Natural Resources Agent Rocky Tanner joined the collaboration to teach the inmates gardening.

On a small patch of land just inside the razor-wire fence, inmates in the RSAT program have grown watermelons, squash, peppers and cantaloupes. The topsoil, lime and fertilizer come from donations Tanner secured from local farmers.

As he stood in front of the participants at the end of a recent “Mind Matters” session, tears sprung to Tanner’s eyes as he confessed to rebuffing Cook’s offer to join the program several times because he was intimidated. He’s grown to love his trips inside the fence, he said.

“I help some of the best farmers in the Southeast, but those three little beds in that little bit of dirt out there mean as much to me as the cornfield that produces 355 bushels an acre,” he said. “Don’t ever be afraid to be proud of yourselves.”

“It’s changed the way I look at things,” RSAT participant Gabriel Green said. “They don’t treat us like inmates — they treat us like human beings, and they really want to see us succeed. When you’re treated with love and compassion, it makes you want to do better.”

Looking to the future

Franklin is one of the program’s many success stories.

Shortly after his release, he got a job with the city, and a local church put him up at a nearby hotel for three months. He’s now in his own apartment.

When Fennell-Burley approached him in the park recently, she asked him if he needed anything.

“I could use a mattress,” he said. “I’ve been sleeping on the floor.”

“I can get you a mattress,” she said.

A few minutes later, Cook stopped by and asked him the same question. Without hesitation, Franklin said he needed some furniture.

“I can get a sofa and end tables for you,” she told him. Jail personnel and local churches chipped in as well, and furniture was delivered the next day.

“This entire community has embraced this program,” Cook said. “We’re really working on the whole person and giving them a reason to be proud of themselves. It has truly made a difference.”

Franklin still meets with Wilson and enjoys visits from jail employees, church members and RSAT program leaders who happen upon him picking up litter in the park or around town. He talks now about getting training for additional jobs.

He’s asked what he thinks about when he’s out in the park all by himself, raking leaves and picking up trash, or sitting alone at home.

“I think about God being good to me,” he said, the train whistle fading in the distance. “Every day I look back and think about that program. I asked for help, and they were there with the help. That program saved my life.”