Professor challenges students on diet culture

Not long after coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic hit the news, phrases like “quarantine-15” and “fattening the curve” began popping up on social media.

A reference to weight gained during stay-at-home orders, a quick hashtag search of these phrases turns up thousands of posts, many of them “before and after” memes and at-home workouts designed to help stem weight gain.

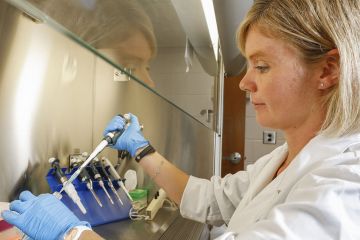

The content, most of it created for lighthearted laughs, highlights the country’s fixation on diet culture, which can be harmful to many but particularly for marginalized identities, said Emma Laing, clinical associate professor and director of dietetics in the University of Georgia College of Family and Consumer Sciences.

“Poking fun about gaining weight perpetuates the idea that thinner bodies are more disciplined, healthier and more worthy of attention, and this is simply untrue,” Laing said. “The thin ideal standards of beauty are unrealistic for people who are genetically larger.”

Another hidden message is the assumption that people have the privilege of focusing on health goals at the moment, Laing said. The messages also ignore critical issues like socioeconomic status, food insecurity and compromised air and water quality that can lead to stress and chronic illness, she added.

“Many individuals have had drastic changes to their work demands, are experiencing financial hardships or have legitimate concerns for their safety, so concerns about healthy eating or exercise might not be taking precedence,” Laing said.

Preoccupation with diet culture is an emerging topic in the dietetics field, one that is shifting how nutrition professionals view weight and body image.

Many professionals, including Laing, entered the field because they wanted to do their part in combatting obesity.

“During my dietetics education, we were instructed to help people lose weight,” Laing said. “However, the field is evolving to a place where body kindness, social justice, diversity and inclusion are shifting this paradigm and it’s important that students have exposure to this discussion.”

Even before the pandemic had spread to the U.S., Laing’s students were learning about weight-inclusive care, which prioritizes well-being over weight and having access to non-stigmatizing health care.

They discuss how dieting and weight stigma can lead to harmful effects, such as repeated cycles of weight loss and regain, reduced self-esteem and disordered eating behaviors.

Students also learn the traditional weight-normative approach, with an emphasis on body weight in defining health and disease management, including diet, exercise and behavior change.

“While weight-normative strategies – pursuing weight loss to improve health – elicit long-term successes for some individuals, many are unable to maintain this,” Laing said. “Using body weight alone as a measure of success can backfire, particularly if indicators like blood pressure, blood sugar and cholesterol levels improve regardless of changes in weight.”

Laing’s students, primarily dietetics and nutritional sciences majors, also address weight bias in health care and the psychological stress it can cause patients.

“Stressors caused by any type of discrimination, such as weightism, sexism and racism perpetuate fat phobia and chronic illness,” she said. “Students need to ask themselves how useful they will feel as a practitioner if patients avoid coming to your office because they fear being shamed due to their weight.”

Laing said it’s important for students to think critically about the potential benefits or harm of dieting for weight loss and then figure out for themselves where they fall on this continuum of treatment approaches.

“I want students to feel comfortable with the discomfort of challenging diet culture and understanding that the concept of health includes mental health as well as other aspects beyond simply body size,” she said.

Regardless of where they stand on these approaches, Laing encourages her students to eliminate any external messages that make them feel guilty or negative about how their body looks.

“Fill your newsfeed with body-positive images that encourage self-compassion, particularly during this time,” Laing said. “Amplifying the messages from underrepresented health professionals on social media, directly from those who have lived experience, is also important to broaden students’ cultural awareness and provide a space that is inclusive of the many ways we can approach health.”

If a person is uncomfortable with how their body has changed over the last few months, Laing suggests seeking guidance from a registered dietitian who can help them achieve wellness goals.

At UGA, students can access nutrition counseling through Dining Services, the University Health Center or the ASPIRE Clinic. They can also become involved with the BeYou Peer Educator program, which helps to promote body positivity on campus.

“Developing eating and activity habits that are enjoyable and best support overall health should be the primary goal for those who are able,” she said.

Poking fun about gaining weight perpetuates the idea that thinner bodies are more disciplined, healthier and more worthy of attention, and this is simply untrue.